Improving seabed monitoring through standardised imaging and AI analysis: SEA-AI

This project sought to determine how underwater imagery could be captured more effectively; to develop a standard operating procedure that would help operators consistently produce clear, high-quality video suitable for both human and automated analysis; and to create AI-assisted tools capable of identifying key biological features associated with selected Priority Marine Features.

Project team

Partners: University of Highlands & Islands, Scottish Sea Farms, Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA), NatureScot, Bakkafrost Scotland, The Data Lab

Authors and key contributors: John Halpin, Thomas A. Wilding, Malcolm Price, Jack Henry, Chris Webb, Marion Harrald, Liam Wright, Ben Seaman, Janina Costa, Sarah Riddle

Case study

Download PDF

BACKGROUND

In the 2023 Vision for Sustainable Aquaculture, the Scottish Government set out its aspirations for the aquaculture sector to be world-leading by 2045 through the responsible and sustainable way it operates. The Scottish finfish farming sector has also stated an aim to significantly increase its economic contribution by 2030, a target that can incorporate both expansion of existing farms and the establishment of new sites. Such growth also means continuing to demonstrate to regulators that the development is environmentally sustainable.

Regulatory bodies, the Scottish Environment Protection Agency (SEPA) and NatureScot, rely heavily on seabed imagery to assess whether Priority Marine Features (PMFs) are present near proposed farm locations. These habitats include sensitive species and biotopes that could be affected by farming operations and other human activities.

In 2022, SEPA’s draft baseline survey design significantly increased the length of seabed video required for farm applications, rising by approximately 400% to around three kilometres of footage for expansion applications. Larger bespoke surveys are required for new developments. Substantial volumes of imagery must be reviewed manually, and surveys may need to be repeated when video quality is insufficient. This creates delays and increased costs for both businesses and regulators, amplifying the need for more efficient and standardised approaches.

The Streamlined and Efficient Artificial Intelligence-Assisted Underwater Video Analysis project (SEA-AI) was designed to address these challenges. Supported by SAIC and The Data Lab, and led by SAMS in collaboration with Scottish Sea Farms, Bakkafrost Scotland, SEPA and NatureScot, the project sought to advance seabed monitoring technology from demonstration in relevant environments to a deployable prototype usable in operational settings.

AIMS

SEA-AI focused on two clear goals. The first and primary goal was to determine how underwater imagery could be captured more effectively by examining how factors such as platform speed, lighting, orientation and camera configuration affect image quality. From this, the team aimed to develop a Standard Operating Procedure (SOP) that would help operators consistently produce clear, high-quality video suitable for both human and automated analysis.

The second goal was to create AI-assisted tools capable of identifying key biological features associated with selected PMFs. These tools needed to be accurate, rapid and consistent, and capable of processing typical aquaculture survey footage. To ensure practical applicability, SEA-AI also aimed to package these models in formats suitable for industry and regulatory use, considering the cybersecurity and hardware requirements of partner organisations.

Establishing the technical pathway from data capture to AI deployment

The project comprised a number of work packages that moved sequentially from optimising image capture to delivering operational AI tools. Initial work examined how survey conditions influence image quality. A BlueROV2 fitted with dual GoPro Hero 9 cameras and four high-powered lights was flown over a maerl bed near the Creag Islands. Surveys were conducted at different speeds, and orthomosaics (which are large, map-quality images with high detail and resolution, made by combining many smaller images) were later used to confirm true movement and evaluate the degree of motion blur. This experimental setup allowed the team to identify a threshold beyond which the detail in the footage degraded significantly.

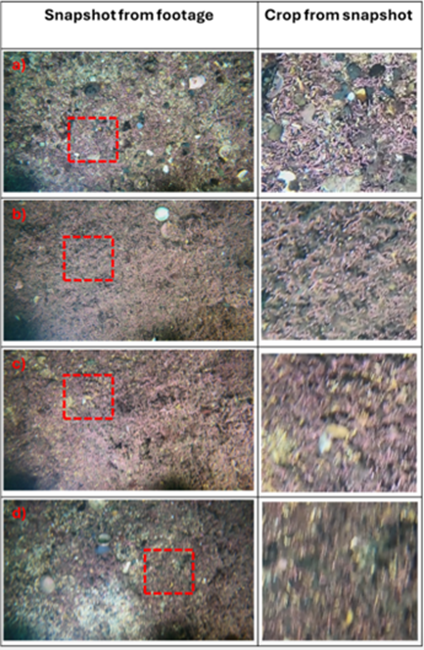

Figure 1. Demonstration of survey speed on image quality. a) 0.16 m/s, 0.31 knots, b) 0.31 m/s, 0.61 knots, c) 0.63 m/s, 1.22 knots and d) 0.86 m/s, 1.60 knots.

Georeferencing was a second foundational component. Two USBL systems were tested: the more economical Cerulean Sonar Locator and the industry-standard Sonardyne Mini-Ranger 2. Each system recorded positional data while the ROV was flown in shallow waters. The Cerulean unit performed intermittently, however, the Sonardyne system produced stable results, demonstrating accuracy suitable for mapping PMF detections in routine survey conditions.

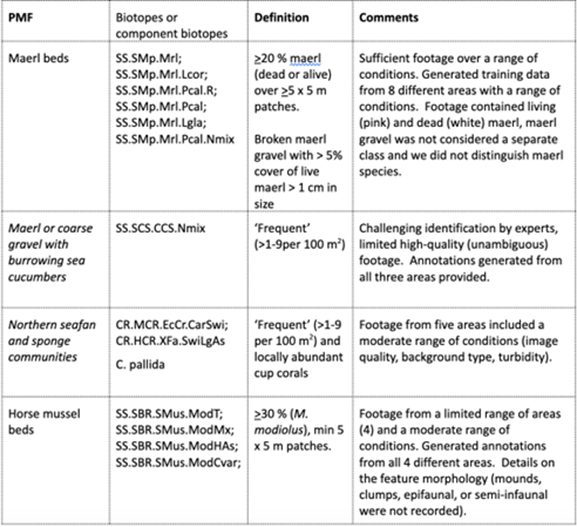

Parallel to this, project partners supplied historic and contemporary seabed footage. This imagery varied widely due to differences in equipment, camera angles, lighting, and sampling methods. Some footage contained metadata overlays and laser scaling features, while other sequences suffered from turbidity, shadows or platform disturbance. The team assessed each dataset for suitability and worked with partners to identify species protected as PMFs that could be reliably targeted using AI. Four were selected: maerl beds; maerl or coarse gravel with burrowing sea cucumbers (Neopentadactyla mixta); northern sea fan (Callistephanus pallida) and sponge communities; and horse mussel (Modiolus modiolus) beds.

Table 1. PMFs included in SEA-AI. All included groups are considered ‘sensitive’ to fish-farm impacts and are associated with sufficient video footage from which to build and evaluate AI-assisted identification models. Full definitions of PMFs are given at the end of this case study.

Annotation formed a substantial element of the project. More than 10,000 images were classified for maerl presence or absence, while approximately 3,000 localised examples of sea fans, sea cucumbers and horse mussels were prepared for object detection. Two MSc students contributed to this full cycle of dataset preparation, annotation, and preliminary modelling.

Figure 2. Illustration of effect of footage quality on appearance of Northern Sea Fan/C. pallida. Left image: poor quality image containing C. pallida, right image: high quality image containing C. pallida including polyp detail.

The modelling approach involved training two types of neural networks. An EfficientNet classifier was trained to distinguish between images containing maerl and those without it. For species requiring localised identification, such as Horse mussels or Northern Sea Fans, a YOLOv5 object detection model was trained to draw bounding boxes around organisms. Model performance was measured through precision, recall and accuracy metrics. For maerl, the team used region-based hold-out tests in which entire survey areas were excluded from training to assess real-world generalisability. For the other species, limited dataset diversity necessitated random splits of training and testing imagery.

Finally, the project focused on usability. To ensure that farmers and regulators could run the models without specialised hardware or elevated IT permissions, the team packaged SEA-AI into two formats. A Google Colab notebook allowed users to run the models in a browser with no installation required, while a standalone executable file enabled offline processing and batch analysis. Both formats required a video file and a formatted CSV containing timestamps and geographical data.

RESULTS

The project demonstrated clear evidence that image quality strongly affects both human interpretation and machine performance. In tests of survey speed, images captured at around 0.3 knots retained the fine detail of maerl thalli, while speeds exceeding 1.2 knots resulted in blurred, unusable imagery. This finding directly informed the SOP and underscored the need for slow, stable flights when collecting video for regulatory purposes.

The georeferencing trials showed that shallow-water environments complicate USBL performance due to reflections and environmental noise. However, the Sonardyne Mini-Ranger 2 consistently produced positional data that met the recommended accuracy threshold of ±10 m.

The performance of the AI model was mixed across the selected PMFs. The maerl classifier achieved approximately 95% accuracy in blind-region testing, demonstrating strong generalisability even when the video was collected under varying conditions or camera configurations. Misclassifications largely stemmed from situations where macroalgae obscured the seabed.

Performance for the object detection model was more variable. The model showed promising results for identifying N. mixta and C. pallida, though both species were challenging under low illumination or oblique angles. False positives occurred when organisms such as sponges or bryozoans looked similar to Northern Sea Fans. The Horse mussel model performed least well, due primarily to the difficulty of distinguishing closed mussels from dark cobbles, and the relatively small number of clear examples in the dataset.

The project successfully advanced the technology readiness level of machine-assisted seabed interpretation. The SEA-AI tool produced georeferenced maps of detections from typical aquaculture survey footage, demonstrating practical utility. Partners have already begun using the maerl model to support their internal assessments.

IMPACT

SEA-AI has delivered a functional, accessible foundation for AI-assisted benthic monitoring in Scotland’s aquaculture sector. The project established clear requirements for high-quality imagery and produced a robust SOP, helping operators capture consistent footage that reduces the risk of surveys being rejected or having to be repeated. By demonstrating that models can reliably detect PMF-associated features, particularly maerl, the project has shown that AI can meaningfully reduce the burden of manual review.

Although human oversight remains essential, especially when interpreting full PMF definitions or resolving ambiguous cases, the SEA-AI tool increases efficiency and provides a high degree of repeatability. It also highlights the need for better, more consistent imagery across the sector, and underscores the importance of collecting footage designed with machine learning in mind.

The project has laid the groundwork for future advances, including more comprehensive species detection, identification of more species, improved object detection performance, and integration with autonomous survey platforms. As underwater imaging becomes cheaper and more widespread, SEA-AI represents an important step toward scalable, technology-enabled environmental monitoring that benefits both regulators and industry.

Links to full definitions (see Table 1):